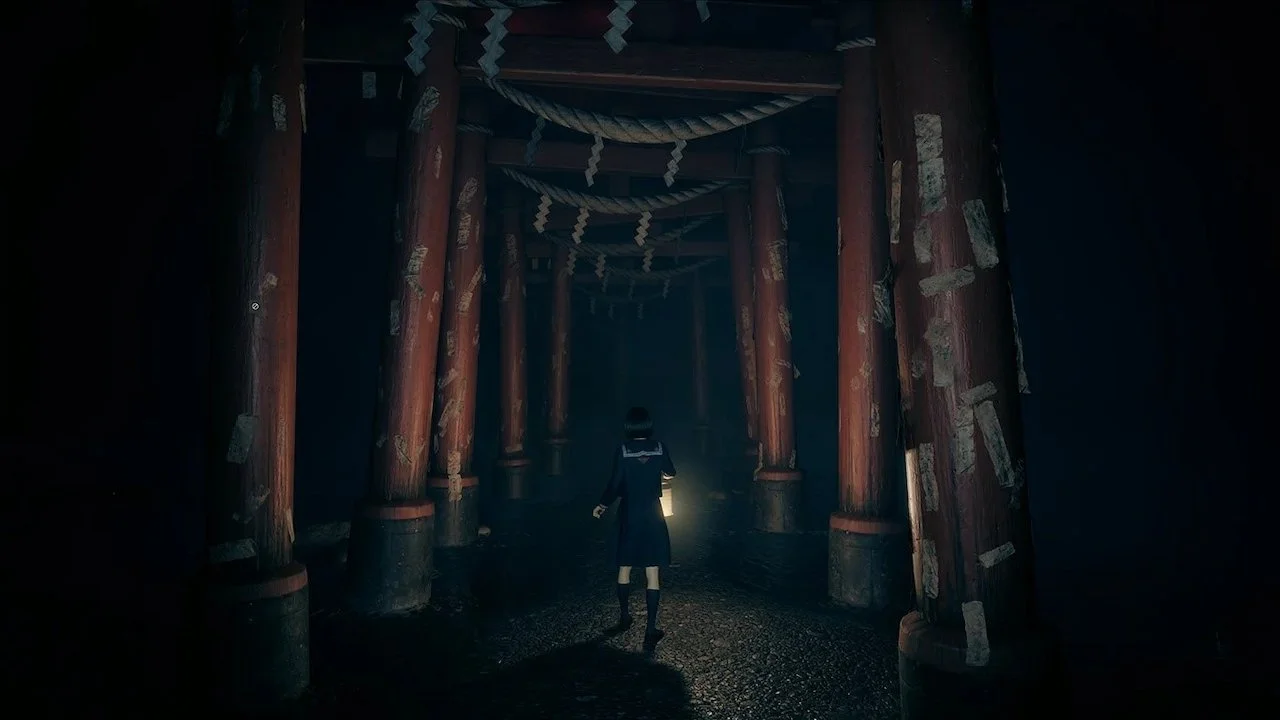

The anticipation of a Silent Hill reboot has been steadily mounting over the past several months, with the rumor mill churning out all manner of speculations. Many have since been quashed, but what we are left with are leaked images purportedly from a new game - seemingly corroborated by the fact that they received a copyright strike from Konami.

Numerous games linked to the franchise are also in development: series creator Keiichiro Toyama is leading Bokeh Game Studio on a new horror game called Slitterhead; and first-person survival horror Abandoned was marketed as a Silent Hill/P.T. style experience, although the developers have seemingly gone dark, suggesting that the game has gone the way of its title. Even Her Story creator Sam Barlow threw his hat into the ring by hinting at a spiritual successor to Silent Hill: Shattered Memories.

So now might be a good time to reflect on what made the revered psychological horror series so special in the first place, and question whether a modern developer will be able to rekindle the essence of the series at its best.

Looking Back at the Series Beginning

Silent Hill was first conceived by Team Silent, an in-house development team within Konami. They were a ragtag bunch: fresh-faced newcomers to the corporate monolith who were thrown together after having been purportedly rejected from other projects within the company. They were tasked with making a Resident Evil rival - or should that be nemesis? - but what they created was far removed from the campy B-movie tone of Capcom's series.

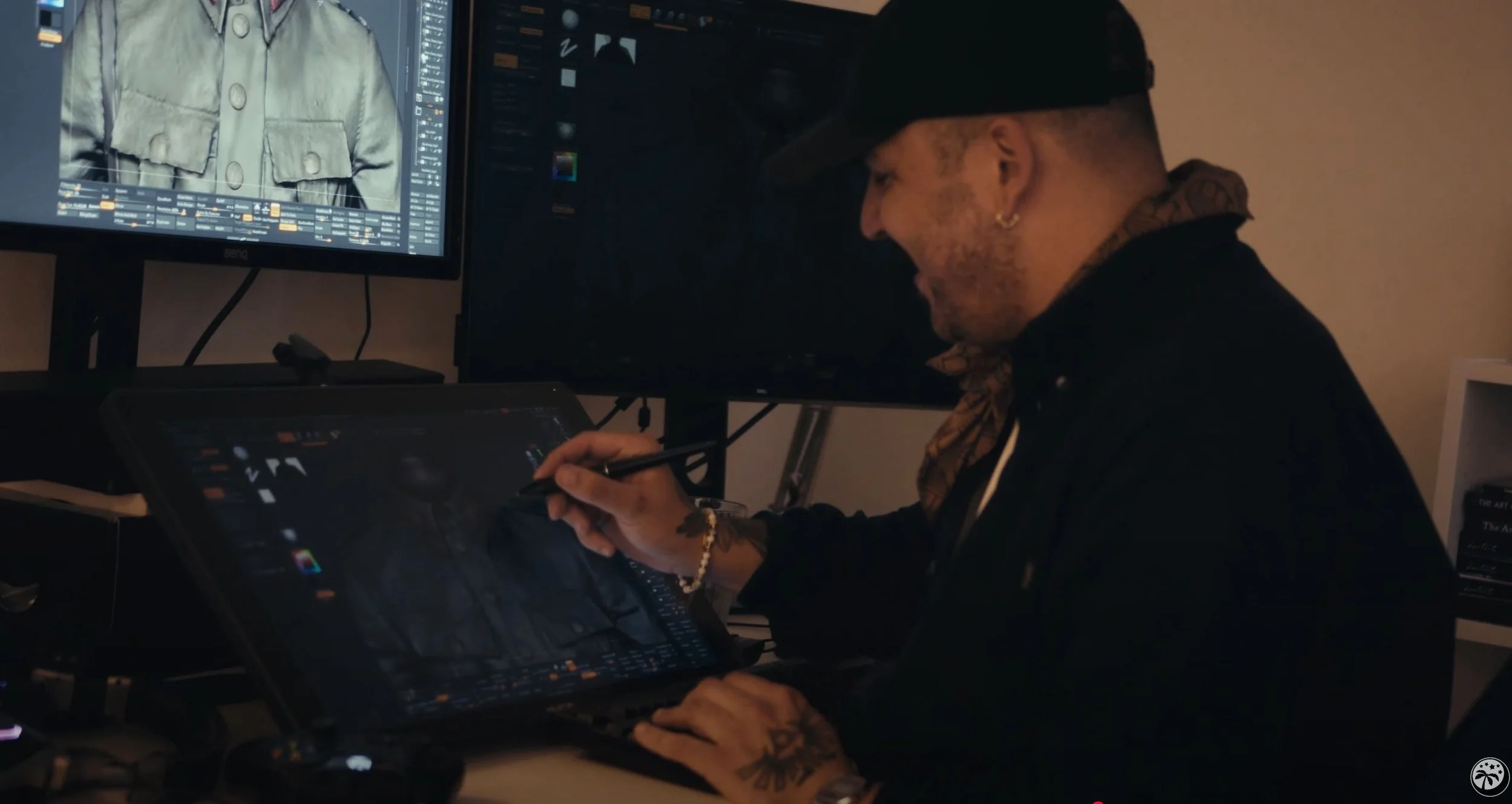

The members didn’t come from your typical developer background. Most were art school graduates, even those who worked on the programming side of things, and even erstwhile composer for the series Akira Yamaoka studied Product and Interior Design at college. Pooling your technical talent from such places would be borderline unthinkable in a modern development studio.

Given their artistic backgrounds, it's no surprise that the team had an eclectic list of influences, all the way from 15th-century Dutch painter Hieronymus Bosch to 20th-century British artist Francis Bacon; even Dostoevsky's classic novel Crime and Punishment, along with 1990 psychological horror film Jacob's Ladder, served as sources of inspiration in the specific case of Silent Hill 2.

It's rare to find big developers namechecking influences like these. Usually, their reference points are other games and movies, not classic works of art or literature; and when they are, they mostly draw from the same pool of names. In the case of horror games, this invariably means making allusions to H.P Lovecraft, which seems to be an unwritten law of horror game development nowadays. Team Silent, however, were citing inspirations quite different from both their peers back then and developers today.

Being young and inexperienced, they were eager to do well and perhaps less jaded than their elders. Relatively speaking, they were also left alone by their superiors and given a high degree of creative control. In Japan, it's known as the ‘Toyota production system’: all employees at every level are given the freedom and responsibility to do their jobs without management breathing down their necks. They are encouraged to contribute their own ideas so as to get the best out of them. That's certainly what Konami got with Silent Hill.

It wasn't exactly plain sailing for the underlings, however. Before joining Team Silent, Takayoshi Sato, an animator tired of not receiving credit for his invaluable expertise, refused to teach the old hands at Konami his 3D animating skills unless he was given a bigger project to work on, such as Metal Gear Solid or Silent Hill. He was duly assigned to the latter.

Even then, Konami still seemed reluctant to give the precocious upstart credit for his work. They wanted him to have a CGI supervisor, which Sato refused as he had completed most of the work already. After an argument with his boss, he was left to finish all the animation work himself. To do this, he needed the computing power of all the 150 Unix systems in the office, which were of course in use by his colleagues during the workday. So once they had left, Sato would use the computers for his rendering work at midnight. He claims to have lived in the office for almost 3 years, sleeping under his desk. It was within this kind of chaotic environment that the revolutionary series was born.

Like all good creative projects, Team Silent was also working within limitations, ones that modern game development simply doesn't face. It’s well known that the fog effect of the first game was a corollary of limiting the draw distance to levels that the Playstation could handle.

Another limitation was the team’s lack of familiarity with American culture. Naoko Sato, who worked on the first Silent Hill as a monster designer, once reflected that she was worried throughout development about depicting a small US town accurately. But it's precisely because it’s a Japanese team's version of a North American town that lends Silent Hill its distinctive character. An outsider's perspective will usually yield more interesting results than an insider’s, as they interpret what they perceive in a unique way.

Also, perhaps conscious of being foreigners to the landscape of their creation, Team Silent paid special attention to every nuance. Going back to the original, it stands out as one of Playstation’s most stylistic and visually complete games. What is most striking is just how detailed the environments are, conjuring the atmosphere of a small American town so well.

With Success Comes a Series

After the surprise success of the first Silent Hill, Team Silent was greenlit to develop the follow-up, this time for the vastly more powerful PlayStation 2, allowing them to stretch their artistic and technical skills to a much greater extent.

Masahiro Ito, who worked as an artist on the first title, was promoted to Art Director for the sequel and took full advantage of the hardware upgrade. He was responsible for designing the monsters, which have had a profound influence on horror games ever since.

Of all the abominations he concocted, his crowning achievement was the infamous Pyramid Head: a large humanoid figure with a brutalist, featureless polyhedron sitting atop his shoulders (who knows if it's a helmet or his actual head?). Ito explained that the purpose of the prismatic design was to elicit a sense of the monster being in constant turmoil.

The monsters of modern horror games are usually cut from the same predictable cloth: Gorey, usually skinless figures that are easy to comprehend, with no real meaning or ideas behind them. The effectiveness of Pyramid Head as a monster, aside from the starkly original design, is that he is both difficult to make sense of yet has a meaning behind him, though it's left to the player's discretion as to what exactly that is. He is most commonly interpreted as some kind of cult executioner who wants to punish protagonist James Sunderland for his sins; a manifestation of his subconscious guilt, as with many of the other monsters in the game.

This lack of providing concrete answers is key to Silent Hill 2's enduring reverence. The principle of 'show don't tell' is something that every great work of art shares. This is especially true in the case of horror, as obliqueness and confusion are fertile ground for fear to take root. Silent Hill 2 leaves plenty of space for individual interpretations, which is why the game continues to be discussed over twenty years later, with many critics and players offering their own viewpoints.

One cannot also fail to mention the much-beloved soundtrack, courtesy of Yamaoka. Despite the hauntingly beautiful melodies, there is always a sense of something being 'off' in his music, as well as being full of atmosphere. It perfectly compliments the setting of a quaint American town gone wrong. His work on the first game was great, but it really took flight on the second, with the whole scope of human emotion encapsulated by his score.

The next couple of entries in the franchise were not bad, but certainly lacked the spark of the first two. Then things took a turn for the decidedly mainstream worse with the western-developed titles. There were some glimmers of hope, such as the aforementioned Shattered Memories, which showed that it was possible to restore the series to its former glory. Otherwise, it was lost to the mire of commercial interests.

Final Thoughts on a Silent Hill Reboot

Following the same formula as every other modern horror game isn’t the way to go for a successful reboot of Silent Hill. The original titles were so idiosyncratic, made by idiosyncratic people under idiosyncratic conditions. They were an antidote to mainstream horror, forgoing cheap thrills in favor of atmosphere, psychological manipulation, and emotional depth.

Unfortunately, modern commercialized game development doesn’t tend to take the kind of risks required to make a game like that. Especially Konami, which for the past decade or so seems hellbent on destroying the legacy of their most beloved franchises. But you never know - maybe they’ve been scouting for art grads again