Discounted review copy provided by Anvil 8 Games

Aetherium is a miniatures board game from Anvil 8 Games that pits two players against each other in a skirmish between warring factions within a digital realm like no other. It’s a mindscape that bends reality to the will of the users.

A game for two players, Aetherium transports gamers to a sci-fi digi-verse that incorporates its theme into the gameplay. Players control a collective of hackers and compete in a roughly 60-minute test of will and tactics. The winner will likely be the player who is best able to manage their programs, coordinate special abilities, and manipulate the virtual reality in a convincing fashion.

Anvil 8 Games released the core game back in 2014 but has since expanded the game to include five additional hacker collectives, expansion sets, and a lot of other content. It’s grown a bunch from its humble beginnings as the small studio has worked to establish an authentic sci-fi miniatures experience to players looking for something deeper in their tabletop gaming.

With anything that involves miniatures, though, there is a higher price to pay, so let’s see if the immersive world of Aetherium lives up to expectations.

STORY

The Aetherium is described as “a place that is no place at all”. It’s the Matrix if this game was released before the 1999 movie. It’s a digital landscape that the human mind can enter and tame, with the right know-how and technology. It’s utopia. It’s hell. It’s whatever you want it to be because there are infinite possibilities in a cyberscape like this.

And humans wouldn’t be humans if they didn’t find a way to colonize the space, capitalize on the opportunity, and make it just as corrupt and conflicted as the real world.

In the base game, two factions in particular fight for control in the quantum realm. The Axiom is a neo-fascist government that has exerted its power over the users that enter into Aetherium. Opposing them are the freedom-fighters of the Nanomei collective, who wield anarchy and fear as tactics in their campaign against the Axiom.

Other hacker collectives vie for control, but the Axiom and the Nanomei are the two most visible and polarizing.

It’s a fascinating setting, with six full pages in the rulebook dedicated to its history. And all of those ideas that manifest in the narrative are reflected in the gameplay. Players will enjoy how thoroughly the two are intertwined.

GAMEPLAY

While miniatures games frequently require time and effort to assemble the miniatures prior to playing and to learn the complex rules of how movement, attack, and territory control functions in the game’s setting, the core gameplay for Aetherium is rather simple.

Two players will start with a hacker collective, select a number of programs—avatars, functions, and subroutines—and face off in a skirmish where the winner is determined through might and strategy.

Breaking that down even further, players take turns activating a program and completing its movement, abilities, and attacks before the next player starts their turn.

So, one play activates a program. Then the other player does the same. That back-and-forth rhythm continues until the endgame is triggered. Depending on the operation chosen by the players, the winner will be determined once they have reached that stage.

A turn is divided into two parts—program activation and re-calibration. Program activation is the ordinary process of using an avatar, function, or subroutine on the playmat, while re-calibration is the refresh phase that occurs whenever a player has depleted their program activation deck (PAD). Players will control 3-5 programs at a time, so the re-calibration happens rather often. Re-calibration will remove cards from deleted programs from the PAD and it will renew depleted RAM that players have used to manipulate schema tiles on the map and to overclock their programs.

If that sounds too technical, or too littered with computer jargon, then don’t worry. It’s easy enough to understand once you read through the rulebook and all of the mechanics are rather well integrated into the lore of the game.

For those that are familiar with miniatures games, then you will likely be even more comfortable than me in dealing with the mechanics of Aetherium, but hobbyist board gamers should not be scared off. Neither should players who are relatively new to the hobby. The rules read easily, and the gameplay flows smoothly.

When programs activate, there are several options available for the player to consider:

1) Moving will direct the program around the map, though it might be influenced by the type of terrain around the program, enemy models adjacent to the program, or other factors that affect the state of the board.

2) Program abilities will either provide offensive augmentation, defensive fortification, or tactical advantages in other aspects of the gameplay. These can be activated with the same Cycle Speed (CS) points as those used by moving.

3) Attacking enemy programs doesn’t cost CS points, but it’s an option once every turn. Melee and ranged combat is dependent on the activated program.

4) Capturing nodes or pylons increases a player’s RAM upon the next re-calibration—and might be part of the overall objective for the operation.

So…… that’s a lot to take in, but it all makes sense pretty quickly and the game plays faster than you’d think. It should last around an hour.

How is the gameplay, though? Probably one of the biggest elements in Aetherium—and the one that makes this more than just a straightforward skirmish game that happens to have miniatures—is the manipulation of schema tiles.

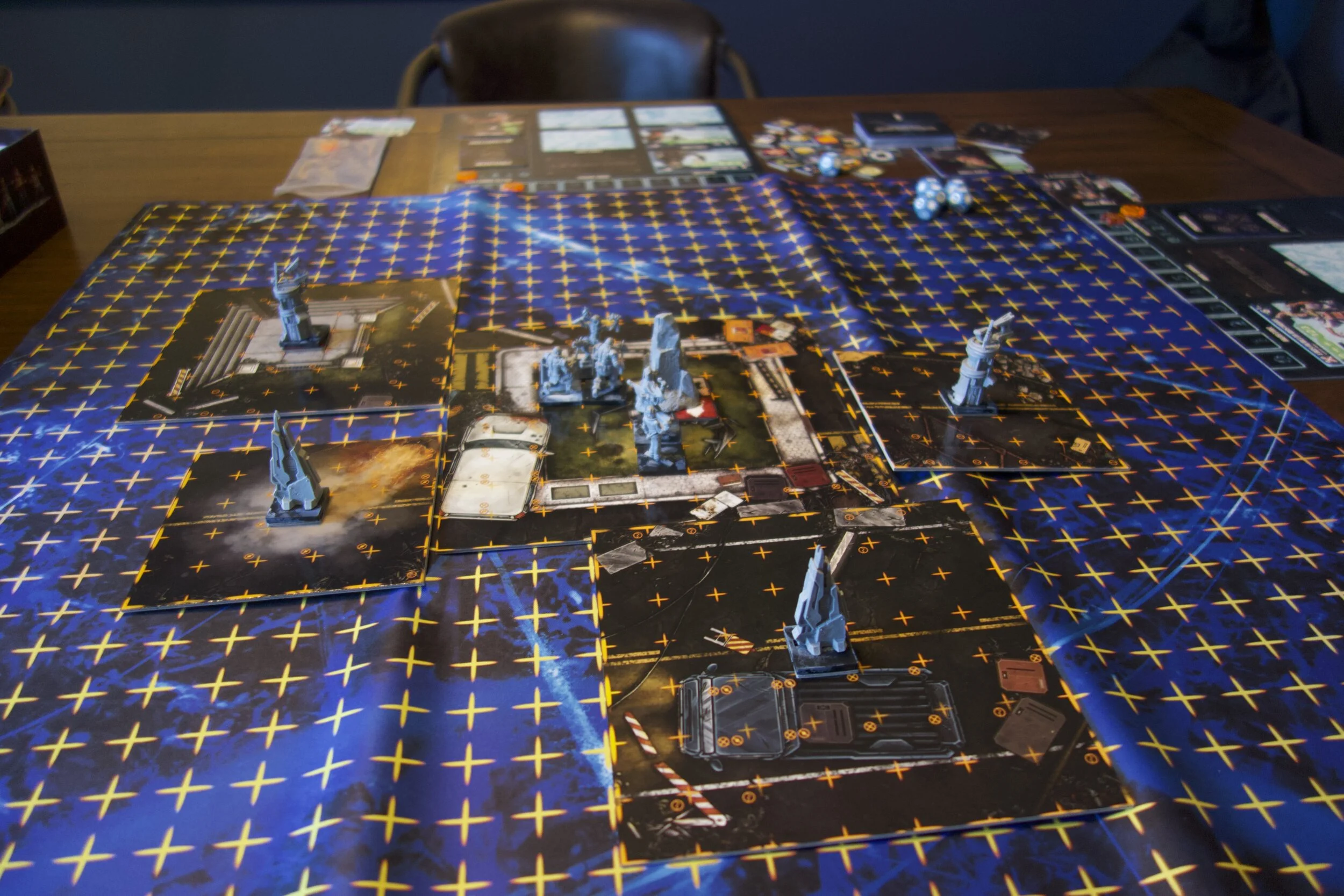

Each player collects RAM over the course of the game, and it’s refreshed during each activation. You can use that to affect your programs, but it’s also available as a way to shift and rotate schema tiles. These tiles are the physical map pieces that are placed on the quantum noise mat. That’s significant because players can greatly affect the state of the board and interfere with their opponent’s plans by changing the orientation of the battlefield.

Is a powerful Avatar about to enter onto a tile with your weakened function or subroutine? Just shift or rotate that tile out of the way, either forcing them to abandon that plan of attack or to waste precious RAM in order to regain that spatial proximity to your programs.

If an objective is out of reach and the way is blocked by a number of enemy models, then a player could try to navigate that distance by changing the orientation of the tiles rather than a full-frontal attack.

Apart from the excellent theme, that one mechanic saves Aetherium from being indistinguishable from a lot of middling games. It’s not just about fighting and moving. It’s about understanding the terrain, recognizing your weaknesses, and exploiting the virtual reality in a way that gives you the advantage over the other player.

It’s clever and it’s not something that you see in many games.

Aetherium is a game of advancing and retreating, capturing and defending, and deleting enemy programs. But the ultimate objective may be different every game. Anvil 8 Games includes different operations in the rulebook that will require players to pursue different targets in a game. One game might require the full deletion of all enemy programs, while another might focus on the player avatars or the territorial control of nodes and pylons.

That variability gives it some depth with regards to gameplay. Players will be able to sit down multiple times and play a different style of game. One might be an all-out battle while another could rely on maneuvering and delay.

Also, the factions play quite differently from each other, so while the combat functions the same, the collective abilities that each avatar, function, and subroutine have are quite different, lending Aetherium an asymmetrical quality that is common in some miniatures games.

VISUALS

If Netrunner and Warhammer 40,000 had a tabletop baby, it might look something like Aetherium. The visuals of the game really do reflect that virtual reality, that cyber… otherness that has given humanity a new place to explore and to exploit.

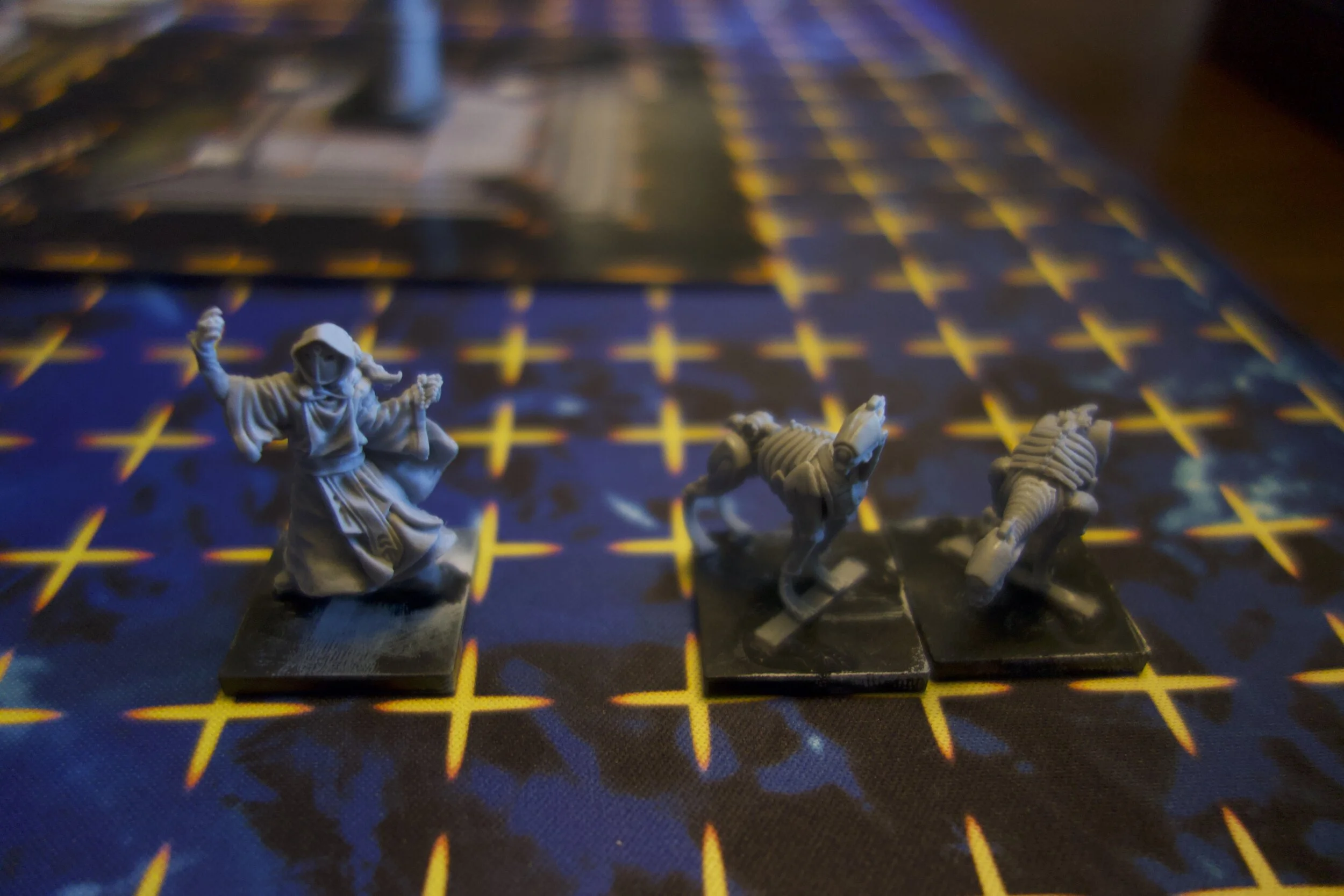

And the miniatures accurately reflect the sensibilities of their collective. The Axiom look like stalwart soldiers in an unrelenting political machine. The Nanomei are anarchists with a penchant for post-apocalyptic fashion. Like Mad Max wastelanders who also know how to hack.

As for the physical game itself, there are places where Aetherium shines—quite literally, with some of the cards and player mats—and there are also weak points to consider as a buyer.

The quantum noise mat is a neoprene mat that folds out into the larger battlezone. The combat dice are 12-sided die with unique symbols that match the aesthetic of a virtual world. The schema tiles are thick pieces of cardboard that will stand up over time through much use. The rulebook is a thick-printed book with plenty of white space, graphic examples, and clear writing.

All of that works in Aetherium’s favor.

It’s in the execution of other elements where I discovered some design choices that I wished were better implemented.

The miniatures, for example.

My previous experience with miniatures was Warhammer 40,000 and the miniatures are molded and packaged very well. With my purchases years ago, I didn’t encounter a lot of extra flash or molding imperfections.

Aetherium doesn’t include the nicest miniatures I’ve used. That’s fine if you’re considering just the base game, but with expansions, other collectives, and extra models players will want to weigh their options. It can quickly stack up to a lot of cash and you want to make sure you’re happy with your miniatures in a miniatures game.

Many pieces I assembled from the base game had a good bit of flash on them or unwieldy connections to the mold bases. This means that I had to take more time to clean up the miniatures.

Some players won’t care about that. Some might not ever prime and paint the miniatures. But it’s something to keep in mind and I did expect a little more from the game given the price point. Either fully assembled miniatures or a better quality of models would have been preferable.

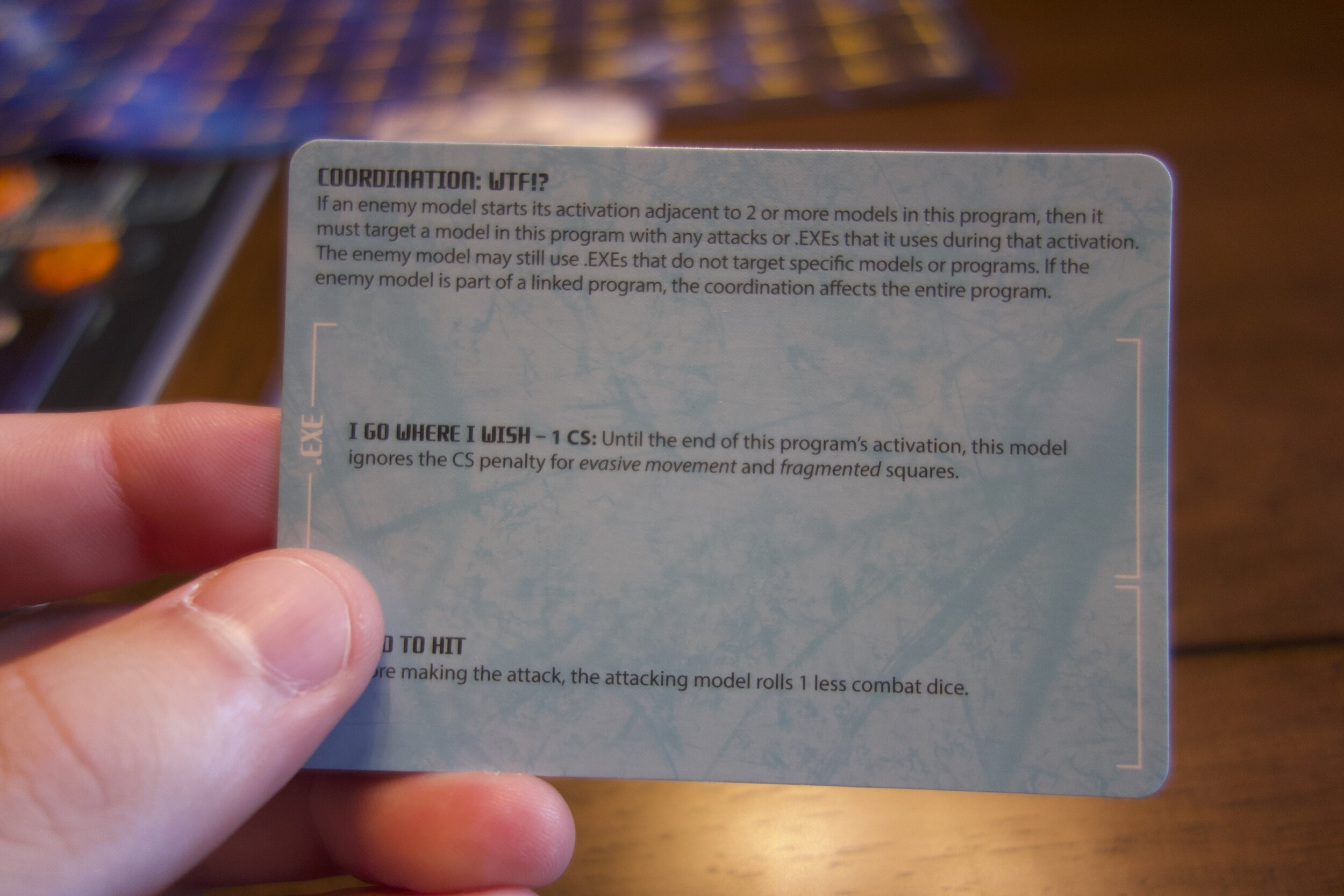

But more frustrating than that was the double-sided nature of the program cards.

The model-specific abilities are all printed on the back of the card. Those are the coordination abilities, .exe abilities, and defensive abilities.

All of these are used every turn, no matter which player is activating their program. So it’s pretty cumbersome to frequently flip the card back and forth. A better choice would have been to redesign the player mat.

The RAM gauge and re-calibration tracker could have easily been incorporated into dials that are adjusted as needed. Those components are found in board games all the time and are super functional. And the extra space means the program cards could have been bigger and that all of the pertinent text could be printed on one side.

For something that’s used so frequently, it shouldn’t sit on the back of the card.

Overall, Aetherium has a magnetic theme that is reflected in the art style of the miniatures, the components, and the rulebook. It’s a job well done by a small but dedicated studio.

However, there are some detractors that could be addressed in a reprint or revised edition. If Anvil 8 Games went back to work with some redesigns, I think this could be a really special game in both form and function.

REPLAYABILITY

After a compelling story and novel gameplay mechanics, this category is where Aetherium surges forward in value.

Since the 2014 release, Anvil 8 Games has introduced five new collectives for a total of seven factions. That’s a lot of potential for players.

And the base game includes six operations (three basic and three advanced) for players to experiment with objective-based gameplay.

So there is a lot of time that you could sink into Aetherium. If you count assembling, priming, and painting miniatures—don’t forget showing them off to your friends—then there is a depth of time and commitment that helps to encourage players to stay engaged.

WHAT IT COULD HAVE DONE BETTER

There are some things I wished were different.

I wanted the miniatures to be of a higher quality. If you buy the base game and two expansions for the two collectives, you’re looking at more than $200. That’s at the price point with premium board games, high-dollar Kickstarter campaigns, and standard miniatures games. So I hoped for more.

Also, the player mats and cards could do with a redesign. Altering the layout of the player mat and the cards would improve the flow of the game and better organize the player area. For a game that takes up a lot of space, this is important.

If these changes were made, then I wouldn’t have any qualms about the price. As it stands, though, one of those aspects needs to change for this to be a really persuasive buy.

One last thing that’s not too big, but it’s something I noticed. The rulebook is quite thick. And daunting to look at. But a lot of it is the artwork of the game and the history of the world and its warring factions. Taking all of that out and printing it in a separate booklet would make the rules look less intimidating. Don’t get rid of that stuff altogether. Reading through that was one of my favorite parts. It’s great stuff. Just maybe isolate it from the rules.

VERDICT

Aetherium stands out. It’s an exciting sci-fi world brought to life where every aspect of the game seems to be tied to the idea of this digital world. The mechanics and the narrative are interconnected in a wonderful way. Some innovative mechanics help to lift it up above the mediocre games that players easily forget. This will be something that surprises you with its quick pace and the brewing cauldron of tactics that players stir together as the skirmish lengthens.

I did notice some issues that could be attributed to a small studio publishing their first game. If Anvil 8 Games goes back and updates some of the components—and the miniatures—with a redesign of higher quality, then this could really stand on the shelf as a special game that players will keep coming back to.

It’s really good. And it could be great. I’m interested to keep an eye on Anvil 8 Games and see what the studio does next, with Aetherium and with other projects.