Imagine you’re a designer for a trading card game. You have only so much space on a card to tell a story, but there’s a problem: you have more story than card. What do you do? You could increase the card size (which is physically impossible) or reduce the story (which means you get fewer ideas across). What about a third option: use two cards! That way you tell the same amount of story, while not actually changing the physical size. That creates whole new problems, so your team puts their heads together to fix them. This process has come to nearly every large TCG at one point or another. Some choose to embrace it and make mistakes, and others chose to pass it by. To introduce this, I’m going to have to mention Yu-Gi-Oh!.

As much as I love teasing Yu-Gi-Oh! players (I am one) and harping on Konami, I have to admit their embracing Fusion and Ritual cards was a bold move. Sure, it worked well in the manga, but bringing it into the physical game presented huge issues. You had to have multiple cards, including Polymerization or the specific ritual card, to get a Monster that wasn’t even very good, considering the cost. Putting the Fusion Monster in the Fusion Deck was a smart move, but a three-for-one is definitely harsh. Enter Synchro Summons! Now you can two-, three-, four- or FIVE-for-one yourself! Advantage! Synchro Monsters tended to be much, much better than Fusion Monsters, however. (Given power creep it was to be expected.) After Syncho Summoning came Xyz and Link, which I won’t go into here because…just look them up. These cards told stories and introduced fun game mechanics, but the card advantage problem has persisted across them all. Is the payout really worth tossing anywhere from two to five cards? In many cases, yes. Powerful cards like Relinquished, Dark Paladin, and Blue-Eyes Ultimate Dragon ruled early games despite the crushing card disadvantage. Largely, however, the results were so weak as to be laughable. (I’m looking at you, Flame Swordsman.)

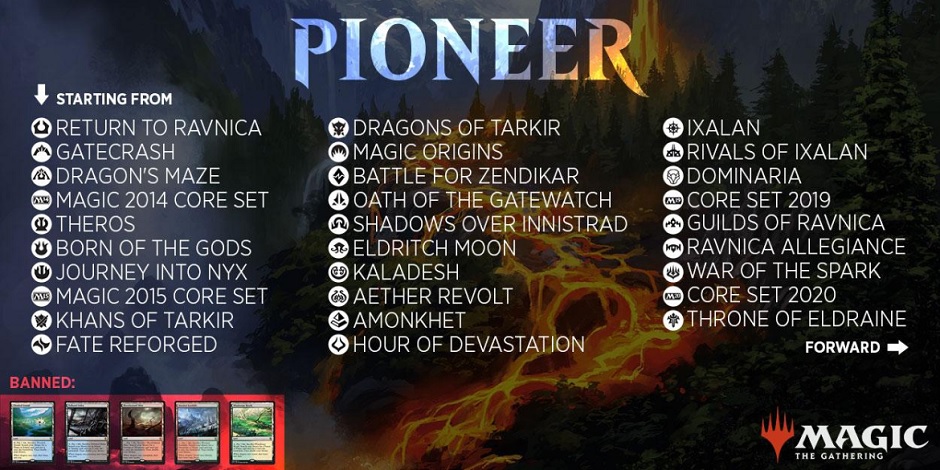

Magic: The Gathering decided to go a slightly different route. Instead of complex rules like Fusion or Synchro Summoning, they just smashed two cards onto one. Invasion started it, Dragon’s Maze introduced Fuse, Hour of Devastation had Aftermath, and now Throne of Eldraine has Adventures (the real reason I wrote this article, to be honest). The thought remains through each iteration of the same mechanic: two effects but one card. We Magic players would throw a fit if Wizards came out with something like Fusions (CARD DISADVANTAGE!!!!!), so they continue to make one-card gimmicks.

Despite massive pushback from…well, everyone making Magic at the time, Mark Rosewater got the Invasion team to make split cards by saying that Magic needed to evolve and make decisions players wouldn’t expect. The Kamigawa flip cards certainly fell into that mindset. Each one was a creature that, when you met a trigger condition, you’d rotate 180°. Suddenly, it’s an entirely different creature (or enchantment)! It wasn’t incredibly popular, and the cards were visually crowded. Years later (and despite massive internal pushback again) Innistrad introduced transforming cards. Instead of rotating the card, you’d turn the card over! This turned out to be so popular it was brought back in Magic Origins, and Ixalan and Shadows over Innistrad blocks. The second set in the Shadows block, Eldritch Moon, had meld, a variation of transform taken from the Un-cards B.F.M. (which inspired the original split cards) and S.N.O.T., as well as the game Duel Masters (which also took inspiration from B.F.M.), and had you turn over two cards to make a single, powerful creature. Long before meld came about, splice allowed you to combine instants and sorceries together by paying additional costs, but you kept the second card. This wasn’t too well received, though mainly because the first card had to have the Arcane subtype and thus restricted which effects you could combine.

Speaking of instants and sorceries, some of the most notable effects that “combine” cards would be the charms. First introduced in Mirage (before Invasion’s split cards), “charm” refers to any instant or sorcery that allows you an array of small effects. While not truly multiple cards, charms allowed incredible flexibility on a single card, which became extremely popular, as the Lorwyn commands and Commander 2015 confluences show. Entwine, introduced in Mirrodin, and escalate, from Eldritch Moon, are variations that allowed you to get more than one effect at a (sometimes) negligible cost.

Magic players are, to borrow the words of Josh Lee Kwai, addicted to value. We talk about two-for-ones, card advantage or disadvantage, flex slots, min/maxing, and other vaguely understandable terms. Smashing two cards into one is about the best thing you could do to make us happy, unless the cards are horribly costed. Magic is rife with mechanics like these; I haven’t even included planeswalkers and sieges. As long as trading card games exist, smushing cards together remains a problem with several interesting solutions.